ISU Graduate Student Studies Food History at World War II Internment Camp Located 121 Miles from ISU

Melissa Lee '14

From 1942 to 1945, more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans were removed from their homes in the Pacific Northwest and sent to live in internment camps after Pearl Harbor. The government saw them as a threat to the military and thought they were too dangerous to live on the west coast. The internment camps were placed on undeveloped federal lands throughout the Midwest so refugees could help develop the land.

The Minidoka Internment Camp was located on 33,000 acres in Jerome County, Idaho, and housed 13,000 people. At first, surrounding communities didn’t want the Japanese-Americans there because they thought that if they were too dangerous to be on the west coast then they were too dangerous for their local communities. Although the local residents initially said no, they realized they needed to utilize the free labor.

Andrew Dunn, an ISU history graduate student, has spent his collegiate career studying the ins and outs of the Minidoka Internment Camp, narrowing his research down to the history of food inside the internment camp.

“There has been research on military and race relations, but nothing with food has been done,” Dunn said. “I wanted to look at Minidoka through a different lens.”

Dunn received his associate’s degree in history from College of Southern Idaho, and chose ISU to continue studying history close to Twin Falls. One of his professors at CSI published a book on Minidoka, and Dunn wanted to learn more and find out ways to get involved.

“I called the National Parks and found out that they had a lot of opportunities to intern,” Dunn said. “They were short staffed, so I got to take a lot more responsibility and play a larger role in projects.”

Dunn has now interned with the National Park Service at the Minidoka Internment Camp for four years helping with site management, tours and planning events. He also helps at the annual Minidoka Pilgrimage, where former incarcerees, their families and friends travel to Minidoka to learn, share memories and ask questions about their experiences. Dunn also serves on the “Friends of Minidoka” board of directors, the agency which oversees interpretation and projects at Minidoka.

One of the key reasons Dunn chose to study the history of food at Minidoka was learning that government records give Japanese-American refugees credit for helping the United States persevere during the war.

“The Japanese-Americans helped save sugar and the food supply in the country,” Dunn said. “Without them, there would be no food to go overseas, and not enough sugar to be used for bombs or ammunition.”

There were limited rations given at the internment camp, and residents had to make their own food. They became completely self-sustainable and had crops, and hog and poultry farms. They would also trade with camps in Utah for beef. Some records show they created their own tofu plant in Minidoka, which was one of the most popular foods they ate at home.

“They needed enough food to eat and also be able to hold onto their culture,” Dunn said. “Food history can be a means of cultural and social history, and helps us better understand how relationships evolved.”

Dunn is also looking into how being in the camp demolished the family structure. Families never sat down to eat together while at camp, because children ran to sit with their friends in the dining hall. Dunn said that this didn’t change once families left the camp.

As part of his research, Dunn had the opportunity to sit down with a woman who moved to the Minidoka Internment Camp when she was 10 years old. Dunn said he was able to learn about her experiences living in the camp as a child, and cross referenced other things he has discovered in his research.

Dunn defended his thesis in May on foodways at the WWII Japanese internment camp in Minidoka. He has also been accepted into the history Ph.D. program at the University of Utah, and he will start in August.

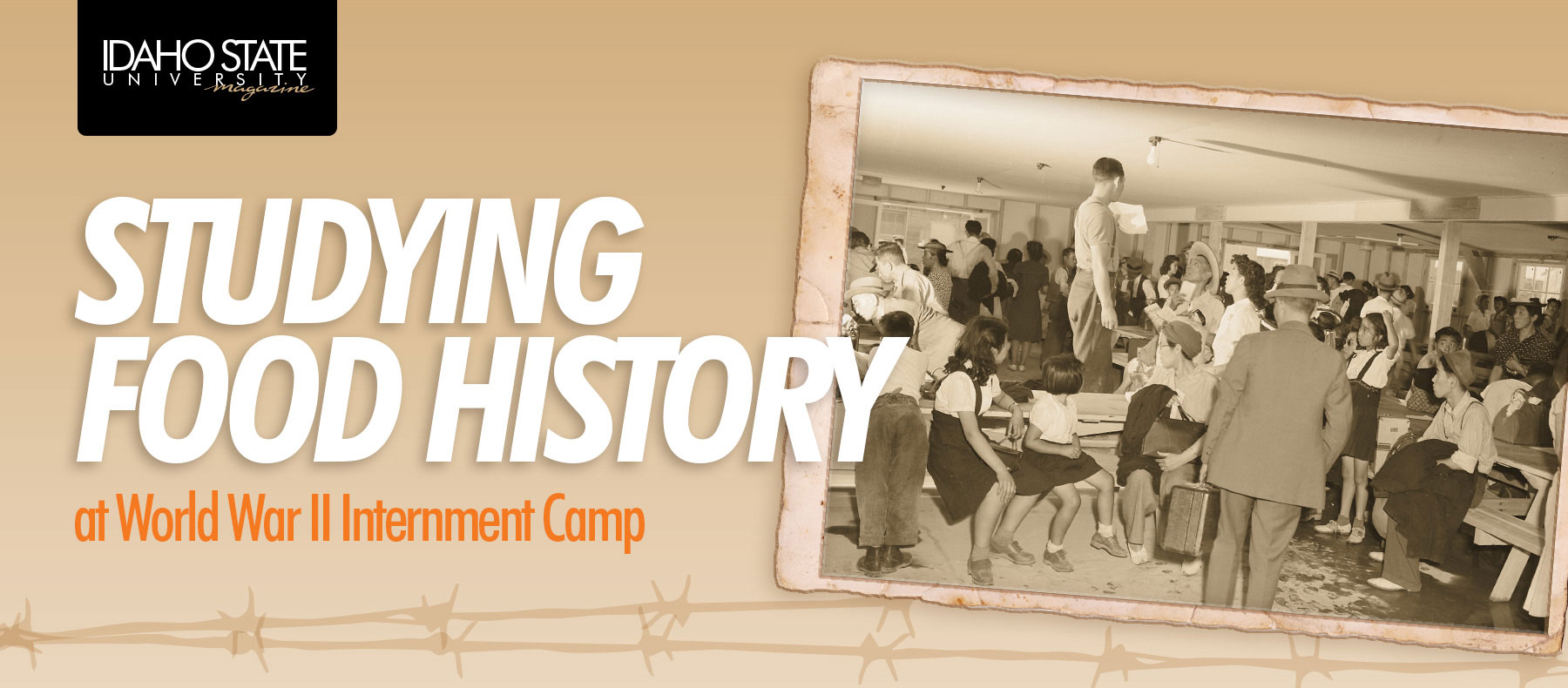

Eden, Idaho. Newly arrived evacuees from the assembly center at Puyallup, Washington, are registered and assigned barrack apartments at this War Relocation Authority center.

Photo by Francis Stewart, War Relocation Authority photographer, Department of the Interior